CLEANLINESS

Cleanliness is both the abstract State of being clean and free from

dirt, and the process of achieving and maintaining that State.

Cleanliness may be endowed with a moral quality, as indicated by the

aphorism "cleanliness is next to godliness," and may be regarded as

contributing to other ideals such as health and beauty.

In emphasizing an ongoing procedure or set of habits for the purpose

of maintenance and prevention, the concept of cleanliness differs

from purity, which is a physical, moral, or ritual State of freedom

from pollutants. Whereas purity is usually a quality of an

individual or substance, cleanliness has a social dimension, or

implies a system of interactions. "Cleanliness," observed Jacob

Burckhardt, "is indispensable to our modern notion of social

perfection." A household or workplace may be said to exhibit

cleanliness, but not ordinarily purity; cleanliness also would be a

characteristic of the people who maintain cleanness or prevent

dirtying.

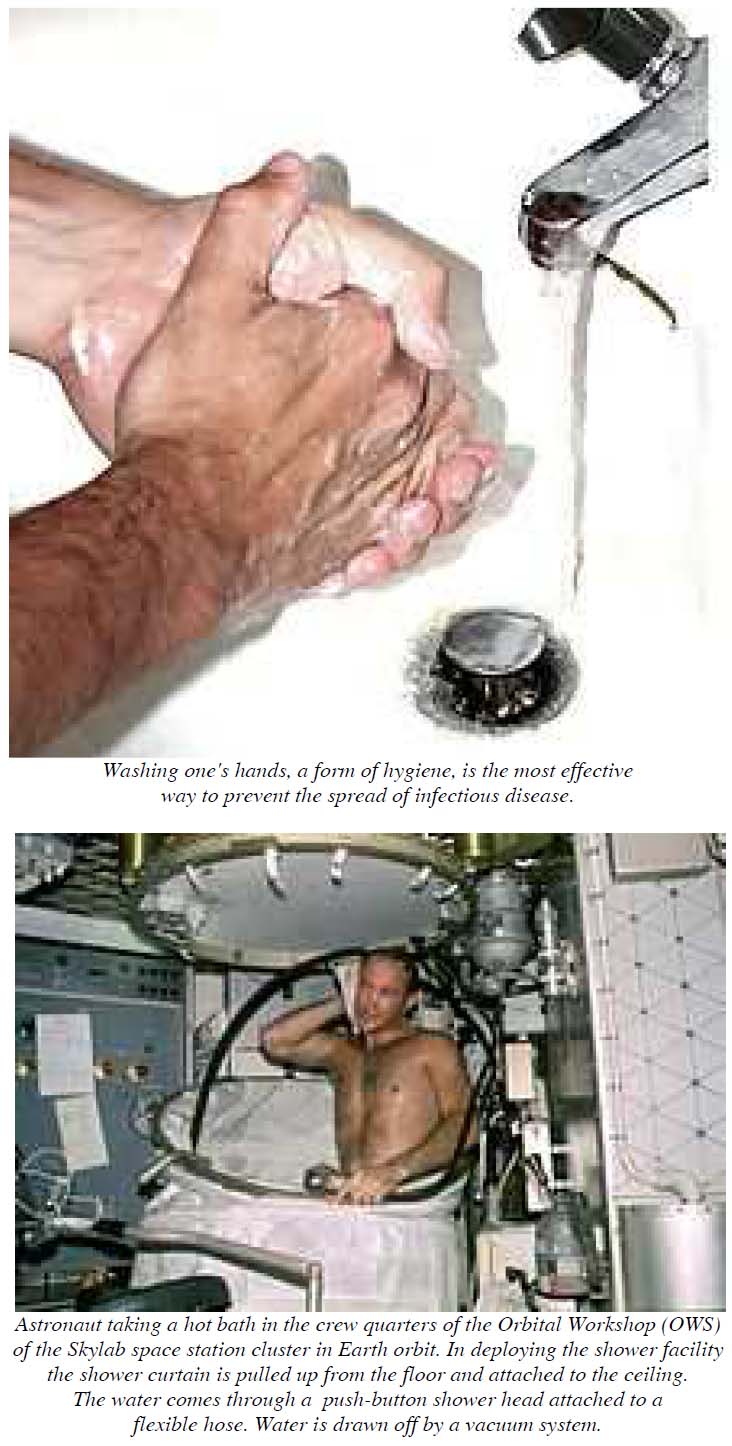

On a practical level, cleanliness is thus related to hygiene and

disease prevention. Washing is one way of achieving physical

cleanliness, usually with water and often some kind of soap or

detergent. Procedures of cleanliness are of utmost importance in

many forms of manufacturing.

As an assertion of moral superiority or respectability, cleanliness

has played a role in establishing cultural values in relation to

social class, humanitarianism, and cultural imperialism.

In Islam

There are many verses in the Quran which discuss cleanliness. For

example, “…Truly, Allah loves those who turn to Him constantly and

He loves those who keep themselves pure and clean” (2:222). And,

“…In mosque there are men who love to be clean and pure. Allah loves

those who make themselves clean and pure” (9:108).

Hinduism

In Hinduism,cleanliness is an important virtue, and all Hindus must

have taken a bath before entering temples in order to seek

blessings.They also wash their feet before entering the temple as

according to the Puranas,the demon kali is believed to reside on the

hind of the feet.In some Orthodox hindu households,taking a bath

after visiting a funeral is required as some hindus believe that it

is an inauspicious thing to witness and the inauspiciousness would

follow.This is also related to the pollution of the River Ganges.

Hindus also clean their homes particularly well in preparing to

celebrate Diwali each year as they believe that it brings good luck

.Most Hindus also believe that keeping your house clean and great

devotion are gestures to welcome the Goddess Lakshmi to their abode

to stay.Some orthodox hindus refrain from cleaning their houses on a

Friday as it is a day dedicated to Goddess Lakshmi and cleaning

homes on that day is considered inauspicious,so they are allowed to

clean their homes on the rest of the days. Tamil people also keep

their homes clean in preparation for pongal(see Bhogi Pandigai).

Hygiene

Since the germ theory of disease, cleanliness has come to mean an

effort to remove germs and other hazardous materials. A reaction to

an excessive desire for a germ-free environment began to occur

around 1989, when David Strachan put forth the "hygiene hypothesis"

in the British Medical Journal. In essence, this hypothesis

holds that dirt plays a useful role in developing the immune system;

the fewer germs people are exposed to in childhood, the more likely

they are to get sick as adults. The valuation of cleanliness,

therefore, has a social and cultural dimension beyond the

requirements of hygiene for practical purposes.

Industry

In industry, certain processes such as those related to integrated

circuit manufacturing, require conditions of exceptional cleanliness

which are achieved by working in cleanrooms. Cleanliness is

essential to successful electroplating, since molecular layers of

oil can prevent adhesion of the coating. The industry has developed

specialized techniques for parts cleaning, as well as tests for

cleanliness. The most commonly used tests rely on the wetting

behaviour of a clean hydrophillic metal surface. Cleanliness is also

important to vacuum systems to reduce outgassing. Cleanliness is

also crucial for semiconductor manufacturing.

What is Hygiene ?

Hygiene (which comes from the name of the Greek goddess of health,

Hygieia), is a set of practices performed

for the preservation of health.

Whereas in popular culture and parlance it can often mean mere

'cleanliness', hygiene in its fullest and original meaning goes much

beyond that to include all circumstances and practices, lifestyle

issues, premises and commodities that engender a safe and healthy

environment. While in modern medical sciences

there is a set of standards of hygiene recommended for different

situations, what is considered hygienic or not can vary between

different cultures, genders

and etarian groups. Some regular

hygienic practices may be considered good habits

by a society while the neglect of hygiene can be considered

disgusting, disrespectful or even threatening.

Sanitation in its current US popular

meaning is often (incorrectly) taken to be merely the hygienic

disposal and treatment by the civic authority of potentially

unhealthy human waste, such as

household garbage and sewage, and the maintenance of the sewerage

and drainage infrastructure. In the UK the term 'sanitation' has

unfortunately come closer to meaning water and waste plumbing and

disposal, and it is not used to include garbage collection and

disposal. The full and proper meaning of 'sanitation' is closer to

the full meaning of 'hygiene' and includes the control of water and

air quality; vectors; healthful housing; safe products; safe food

and working conditions. The more recent broad term 'environmental

health' equates to the original meaning of sanitation.

First attested in English in 1677s, the word hygiene comes

from the

French hygiene, the

latinisation of the Greek

ὑγιεινή (τέχνη) hugieinē technē, meaning "(art) of health",

from ὑγιεινός hugieinos, "good for the health, healthy", in

turn from ὑγιής (hugiēs), "healthful, sound, salutary,

wholesome". In ancient Greek religion,

Hygeia (Ὑγίεια) was the

personification of health.

Concept of hygiene

Hygiene is an old concept related to medicine, as well as to

personal and professional care practices related to most aspects of

living. In medicine and in home (domestic) and everyday life

settings, hygiene practices are employed as preventative measures to

reduce the incidence and spreading of disease. In the manufacture of

food, pharmaceutical, cosmetic and other products, good hygiene is a

key part of

quality assurance i.e. ensuring that the

product complies with microbial specifications appropriate to its

use. The terms cleanliness (or

cleaning) and hygiene are often used interchangeably, which can

cause confusion. In general, hygiene mostly means practices that

prevent spread of disease-causing organisms. Since cleaning

processes (e.g., hand washing) remove infectious microbes as well as

dirt and soil, they are often the means to achieve hygiene. Other

uses of the term appear in phrases including: body hygiene,

personal hygiene, sleep hygiene,

mental hygiene, dental

hygiene,

and occupational hygiene,

used in connection with public health.

Hygiene is also the name of a branch of science that deals

with the promotion and preservation of health, also called hygienic.

Hygiene practices vary widely, and what is considered acceptable in

one culture might not be

acceptable in another.

Medical hygiene

Medical hygiene pertains to the hygiene practices related to the

administration of medicine, and medical care, that prevents or

minimizes disease and the spreading of disease.

Medical hygiene practices include:

-

Isolation

or

quarantine

of infectious persons or materials to prevent spread of

infection.

-

Sterilization

of instruments used in

surgical procedures.

-

Use of protective

clothing and barriers, such as

masks,

gowns,

caps,

eyewear

and

gloves.

-

Proper

bandaging

and

dressing

of

injuries.

-

Safe

disposal

of

medical waste.

-

Disinfection of

reusables (i.e. linen, pads, uniforms)

-

Scrubbing up,

hand-washing, especially in an operating room, but in more

general health-care settings as well, where diseases can be

transmitted

Most of these practices were developed in the 19th century and were

well established by the mid-20th century. Some procedures (such as

disposal of

medical waste) were refined in response

to late-20th century disease outbreaks, notably AIDS

and Ebola.

Home and everyday life hygiene

Home hygiene pertains to the hygiene practices that prevent or

minimize disease and the spreading of disease in home (domestic) and

in everyday life settings such as social settings, public transport,

the work place, public places etc.

Hygiene in home and everyday life settings plays an important part

in preventing spread of infectious diseases. It includes procedures

used in a variety of domestic situations such as hand hygiene,

respiratory hygiene, food and water hygiene, general home hygiene

(hygiene of environmental sites and surfaces), care of domestic

animals, and home healthcare (the care of those who are at greater

risk of infection).

At present, these components of hygiene tend to be regarded as

separate issues, although all are based on the same underlying

microbiological principles. Preventing the spread of infectious

diseases means breaking the chain of infection transmission. The

simple principle is that, if the chain of infection is broken,

infection cannot spread. In response to the need for effective codes

of hygiene in home and everyday life settings the International

Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene has developed a

risk-based approach (based on Hazard

Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP),

which has come to be known as "targeted hygiene". Targeted hygiene

is based on identifying the routes of spread of pathogens in the

home, and applying hygiene procedures at critical points at

appropriate times to break the chain of infection.

The main sources of infection in the home are people (who are

carriers or are infected), foods (particularly raw foods) and water,

and domestic animals (in western countries more than 50% of homes

have one or more pets). Additionally, sites that accumulate stagnant

water—such as sinks, toilets, waste pipes, cleaning tools, face

cloths—readily support microbial growth, and can become secondary

reservoirs of infection, though species are mostly those that

threaten "at risk" groups.

Germs (potentially infectious bacteria,

viruses etc.) are constantly shed from these sources via mucous

membranes, faeces, vomit, skin scales, etc. Thus, when circumstances

combine, people become exposed, either directly or via food or

water, and can develop an infection. The main "highways" for spread

of germs in the home are the hands, hand and food contact surfaces,

and cleaning cloths and utensils. Germs can also spread via clothing

and household linens, such as towels. Utilities such as toilets and

wash basins, for example, were invented for dealing safely with

human waste, but still have risks associated with them, which may

become critical at certain times, e.g., when someone has sickness or

diarrhea. Safe disposal of human waste is a fundamental need; poor

sanitation is a primary cause of

diarrhea disease in low income communities. Respiratory viruses and

fungal spores are also spread via the air.

Good home hygiene means targeting hygiene procedures at critical

points, at appropriate times, to break the chain of infection i.e.

to eliminate germs before they can spread further. Because the

"infectious dose" for some pathogens can be very small (10-100

viable units, or even less for some viruses), and infection can

result from direct transfer from surfaces via hands or food to the

mouth, nasal mucosa or the eye, 'hygienic cleaning' procedures

should be sufficient to eliminate pathogens from critical surfaces.

Hygienic cleaning can be done by:

-

Mechanical removal

(i.e. cleaning) using a

soap or

detergent.

To be effective as a hygiene measure, this process must be

followed by thorough rinsing under running water to remove germs

from the surface.

-

Using a process or

product that inactivates the pathogens in situ. Germ kill is

achieved using a "micro-biocidal" product i.e. a

disinfectant

or

antibacterial

product or

waterless hand sanitizer,

or by application of heat.

In some cases combined germ removal with kill is used, e.g.

laundering of clothing and household linens such as towels and

bedlinen.

Hand hygiene

Hand hygiene is defined as

hand washing or washing hands and nails

with soap and water or using a waterless hand sanitizer.

Hand hygiene is central to preventing spread of infectious diseases

in home and everyday life settings.

In situations where hand washing with soap is not an option (e.g.

when in a public place with no access to wash facilities), a

waterless hand sanitizer such as an

alcohol hand gel can be used. They

can also be used in addition to hand washing, to minimize risks when

caring for "at risk" groups. To be effective, alcohol hand gels

should contain not less than 60%v/v alcohol. Hand sanitizers are not

an option in most developing countries. In situations with limited

water supply, there are water-conserving solutions, such as tippy-taps.

(A tippy-tap is a simple technology using a jug suspended by a rope,

and a foot-operated lever to pour a small amount of water over the

hands and a bar of soap.) In low-income communities, mud or ash is

sometimes used as an alternative to soap.

The World Health Organization recommends hand washing with ash if

soap is not available in emergencies, schools without access to

soap and other difficult situations like post-emergencies where use

of (clean) sand is recommended too. Use of ash is common and has in

experiments been shown at least as effective as soap for removing

bacteria.

Respiratory hygiene

Correct respiratory and

hand hygiene when coughing and sneezing

reduces the spread of germs particularly during the cold

and flu season.

-

Carry tissues and use

them to catch coughs and sneezes

-

Dispose of tissues as

soon as possible

-

Clean your hands by

hand washing

or using an alcohol

hand sanitizer.

Food hygiene at home

Food hygiene is concerned with the hygiene practices that prevent

food poisoning. The five key principles of food hygiene, according

to

WHO, are:

1.

Prevent contaminating food with mixing chemicals spreading from

people, pets, and pests.

2.

Separate raw and cooked foods to prevent contaminating the cooked

foods.

3.

Cook foods for the appropriate length of time and at the appropriate

temperature to kill pathogens.

4.

Store food at the proper temperature.

5.

Use safe water and raw materials

Household water treatment and safe storage

Household water treatment and safe storage ensure drinking water is

safe for consumption.

Drinking water quality remains a

significant problem, not only in developing countries but also in

developed countries; even in the European region it is estimated

that 120 million people do not have access to safe drinking

water. Point-of-use water quality

interventions can reduce diarrheal disease in communities where

water quality is poor, or in emergency situations where there is a

breakdown in water supply. Since water can become contaminated

during storage at home (e.g. by contact with contaminated hands or

using dirty storage vessels), safe storage of water

in the home is also important.

Methods for treatment of drinking water, include:

1.

Chemical disinfection using chlorine or iodine

2.

Boiling

3.

Filtration using ceramic filters

4.

Solar disinfection - Solar disinfection is an effective method,

especially when no chemical disinfectants are available.

5. UV

irradiation - community or household UV systems may be batch or

flow-though. The lamps can be suspended above the water channel or

submerged in the water flow.

6.

Combined flocculation/disinfection systems – available as sachets of

powder that act by coagulating and flocculating sediments in water

followed by release of chlorine.

7.

Multibarrier methods – Some systems use two or more of the above

treatments in combination or in succession to optimize efficacy.

Hygiene in the kitchen, bathroom and toilet

Routine cleaning of (hand, food and drinking water) sites and

surfaces (such as toilet seats and flush handles, door and tap

handles, work surfaces, bath and basin surfaces) in the kitchen,

bathroom and toilet reduces the risk of spread of germs. The

infection risk from the toilet itself is not high, provided it is

properly maintained, although some splashing and aerosol formation

can occur during flushing, particularly where someone in the family

has diarrhea. Germs can survive in the scum or scale left behind on

baths and wash basins after washing and bathing.

Water left stagnant in the pipes of showers can be contaminated with

germs that become airborne when the shower is turned on. If a shower

has not been used for some time, it should be left to run at a hot

temperature for a few minutes before use.

Thorough cleaning is important in preventing the spread of fungal

infections. Molds can live on wall and floor tiles and on shower

curtains. Mold can be responsible for infections, cause allergic

responses, deteriorate/damage surfaces and cause unpleasant odors.

Primary sites of fungal growth are inanimate surfaces, including

carpets and soft furnishings. Air-borne fungi are usually associated

with damp conditions, poor ventilation or closed air systems.

Cleaning of toilets and hand wash facilities is important to prevent

odors and make them socially acceptable. Social acceptance is an

important part of encouraging people to use toilets and wash their

hands.

Laundry hygiene

Laundry hygiene pertains to the practices that prevent or minimize

disease and the spreading of disease via soiled clothing and

household linens such as towels. Items most likely to be

contaminated with pathogens are those that come into direct contact

with the body, e.g., underwear, personal towels, facecloths,

nappies. Cloths or other fabric items used during food preparation,

or for cleaning the toilet or cleaning up material such as faeces or

vomit are a particular risk.

Microbiological and epidemiological data indicates that clothing and

household linens etc. are a risk factor for infection transmission

in home and everyday life settings as well as institutional

settings, although the lack of quantitative data directly linking

contaminated clothing to infection in the domestic setting makes it

difficult to assess the extent of the risk. Although microbiological

data indicates that risks from clothing and household linens are

somewhat less than those associated with hands, hand contact and

food contact surfaces, and cleaning cloths, nevertheless these risks

needs to be appropriately managed through effective laundering

practices. In the home, this routine should be carried out as part

of a multibarrier approach to hygiene which also includes hand,

food, respiratory and other hygiene practices.

Infection risks from contaminated clothing etc. can increase

significantly under certain conditions. e.g. in healthcare

situations in hospitals, care homes and the domestic setting where

someone has diarrhoea, vomiting, or a skin or wound infection. It

also increases in circumstances where someone has reduced immunity

to infection.

Hygiene measures, including laundry hygiene, are an important part

of reducing spread of antibiotic resistant strains. In the

community, otherwise healthy people can become persistent skin

carriers of MRSA, or faecal carriers of enterobacteria strains which

can carry multi-antibiotic resistance factors (e.g. NDM-1 or ESBL-producing

strains). The risks are not apparent until, for example, they are

admitted to hospital, when they can become “self infected” with

their own resistant organisms following a surgical procedure. As

persistent nasal, skin or bowel carriage in the healthy population

spreads “silently” across the world, the risks from resistant

strains in both hospitals and the community increases. In particular

the data indicates that clothing and household linens are a risk

factor for spread of S. aureus (including MRSA and PVL-producing

MRSA strains), and that effectiveness of laundry processes may be an

important factor in defining the rate of community spread of these

strains. Experience in the USA suggests that these strains are

transmissible within families, but also in community settings such

as prisons, schools and sport teams. Skin-to-skin contact (including

unabraded skin) and indirect contact with contaminated objects such

as towels, sheets and sports equipment seem to represent the mode of

transmission.

During laundering, temperature, together with the action of water

and detergent work together to reduce microbial contamination levels

on fabrics. During the wash cycle soil and microbes are detached

from fabrics and suspended into the wash water. These are then

“washed away” during the rinse and spin cycles. In addition to

physical removal, micro-organisms can be killed by thermal

inactivation which increases as the temperature is increased.

Chemical inactivation of microbes by the surfactants and activated

oxygen-based bleach used in detergents also contributes to the

hygiene effectiveness of laundering. Adding hypochlorite bleach in

the washing process also achieves inactivation of microbes. A number

of other factors can also contribute including drying and ironing.

Laundry detergents contain a mix of ingredients including

surfactants, builders, optical brighteners, etc. Cleaning action

arises primarily from the action of the surfactants and other

ingredients, which are designed to maximise release and suspension

of dirt and microbes into the wash liquid, together with enzymes

and/or an activated oxygen-based bleach which digest and remove

stains. Although activated oxygen bleach is included in many powder

detergents to digest and remove stains, it also produces some

chemical inactivation of bacteria, fungi and viruses. As a rule of

thumb, powders and tablets normally contain an activated oxygen

bleach, but liquids, and all products (liquid or powder) used for

“coloureds” do not. Surfactants also exert some chemical

inactivation action against certain species although the extent of

their action is not known.

In 2013 the International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene (IFH)

reviewed some 30 studies of the hygiene effectiveness of laundering

at various temperatures ranging from room temperature to 70 °C,

under varying conditions. A key finding was the lack of

standardisation and control within studies, and the variability in

test conditions between studies such as wash cycle time, number of

rinses etc. The consequent variability in the data (i.e. the

reduction in contamination on fabrics) obtained, in turn makes it

extremely difficult to propose guidelines for laundering with any

confidence, based on currently available data. As a result there is

significant variability in the recommendations for hygienic

laundering of clothing etc. given by different agencies.

Of concern is recent data suggesting that, in reality, modern

domestic washing machines do not reach the temperature specified on

the machine controls.

Medical hygiene at home

Medical hygiene pertains to the hygiene practices that prevents or

minimizes disease and the spreading of disease in relation to

administering medical care to those who are infected or who are more

"at risk" of infection in the home. Across the world, governments

are increasingly under pressure to fund the level of healthcare that

people expect. Care of increasing numbers of patients in the

community, including at home is one answer, but can be fatally

undermined by inadequate infection control in the home.

Increasingly, all of these "at-risk" groups are cared for at home by

a carer who may be a household member who thus requires a good

knowledge of hygiene. People with reduced immunity to infection, who

are looked after at home, make up an increasing proportion of the

population (currently up to 20%). The largest proportion are the

elderly who have co-morbidities, which reduce their immunity to

infection. It also includes the very young, patients discharged from

hospital, taking immuno-suppressive drugs or using invasive systems,

etc. For patients discharged from hospital, or being treated at home

special "medical hygiene" (see above) procedures may need to be

performed for them e.g. catheter or dressing replacement, which puts

them at higher risk of infection.

Antiseptics may be applied to cuts,

wounds abrasions of the skin to prevent the entry of harmful

bacteria that can cause sepsis. Day-to-day hygiene practices, other

than special medical hygiene procedures are no different for those

at increased risk of infection than for other family members. The

difference is that, if hygiene practices are not correctly carried

out, the risk of infection is much greater.

Home hygiene in low-income communities

In the developing world, for decades, universal access to water and

sanitation

has been seen as the essential step in reducing the preventable ID

burden, but it is now clear that this is best achieved by programs

that integrate hygiene promotion with improvements in water quality

and availability, and sanitation.

About 2 million people die every year due to diarrheal diseases,

most of them are children less than 5 years of age. The most

affected are the populations in developing countries, living in

extreme conditions of poverty, normally peri-urban dwellers or rural

inhabitants. Providing access to sufficient quantities of safe

water, the provision of facilities for a sanitary disposal of

excreta, and introducing sound hygiene behaviors are of capital

importance to reduce the burden of disease caused by these risk

factors.

Research shows that, if widely practiced,

hand washing with soap could reduce

diarrhea by almost fifty percent and respiratory infections by

nearly twenty-five percent Hand washing with soap also reduces the

incidence of skin diseases, eye infections like trachoma and

intestinal worms, especially ascariasis and trichuriasis.

Other hygiene practices, such as safe disposal of waste, surface

hygiene, and care of domestic animals, are also important in low

income communities to break the chain of infection transmission.

Disinfectants and antibacterials in home hygiene

Chemical disinfectants are products that

kill germs (harmful bacteria, viruses and fungi). If the product is

a disinfectant, the label on the product should say "disinfectant"

and/or "kills" germs or bacteria etc. Some commercial products, e.g.

bleaches, even though they are technically disinfectants, say that

they "kill germs", but are not actually labelled as "disinfectants".

Not all disinfectants kill all types of germs. All disinfectants

kill bacteria (called bactericidal). Some also kill fungi

(fungicidal), bacterial spores (sporicidal) and/or viruses (virucidal).

An

antibacterial

product is a product that acts against bacteria in some unspecified

way. Some products labelled "antibacterial" kill bacteria while

others may contain a concentration of active ingredient that only

prevent them multiplying. It is, therefore, important to check

whether the product label States that it "kills" bacteria." An

antibacterial is not necessarily anti-fungal or anti-viral unless

this is Stated on the label.

The term

sanitizer

has been used to define substances that both clean and disinfect.

More recently this term has been applied to alcohol-based products

that disinfect the hands (alcohol hand sanitizers).

Alcohol hand sanitizers however are not considered to be effective

on soiled hands.

The term

biocide

is a broad term for a substance that kills, inactivates or otherwise

controls living organisms. It includes antiseptics

and disinfectants, which combat micro-organisms, and also includes

pesticides.

Personal hygiene

Personal hygiene involves those practices performed by an individual

to care for one's bodily health and well being, through cleanliness.

Motivations for personal hygiene practice include reduction of

personal illness, healing from personal illness, optimal health and

sense of well being, social acceptance and prevention of spread of

illness to others. What is considered proper personal hygiene can be

cultural-specific and may change over time. In some cultures

removal of body hair

is considered proper hygiene. Other practices that are generally

considered proper hygiene include bathing regularly, washing hands

regularly and especially before handling food, washing scalp hair,

keeping hair short or removing hair, wearing clean clothing,

brushing one's teeth, cutting finger nails, besides other practices.

Some practices are gender-specific, such as by a woman during her

menstrual cycle. People tend to develop a routine for attending to

their personal hygiene needs. Other personal hygienic practices

would include covering one's mouth when coughing, disposal of soiled

tissues appropriately, making sure toilets are clean, and making

sure food handling areas are clean, besides other practices. Some

cultures do not kiss or shake hands to reduce transmission of

bacteria by contact.

Personal grooming extends personal

hygiene as it pertains to the maintenance of a good personal and

public appearance, which need not necessarily be hygienic. It may

involve, for example, using deodorants or perfume, shaving, or

combing, besides other practices.

Excessive body hygiene

Excessive body hygiene and allergies

The

hygiene hypothesis

was first formulated in 1989 by Strachan who observed that there was

an inverse relationship between family size and development of

atopic allergic disorders – the more children in a family, the less

likely they were to develop these allergies.

From this, he hypothesised that lack of exposure to "infections" in

early childhood transmitted by contact with older siblings could be

a cause of the rapid rise in atopic disorders over the last thirty

to forty years. Strachan further proposed that the reason why this

exposure no longer occurs is, not only because of the trend towards

smaller families, but also "improved household amenities and higher

standards of personal cleanliness".

Although there is substantial evidence that some microbial exposures

in early childhood can in some way protect against allergies, there

is no evidence that we need exposure to harmful microbes (infection)

or that we need to suffer a clinical infection. Nor is there

evidence that hygiene measures such as hand washing, food hygiene

etc. are linked to increased susceptibility to

atopic disease. If this is the case,

there is no conflict between the goals of preventing infection and

minimising allergies. A consensus is now developing among experts

that the answer lies in more fundamental changes in lifestyle etc.

that have led to decreased exposure to certain microbial or other

species, such as helminths, that are important for development of

immuno-regulatory mechanisms. There is still much uncertainty as to

which lifestyle factors are involved.

Although media coverage of the hygiene hypothesis has declined, a

strong ‘collective mindset’ has become established that dirt is

‘healthy’ and hygiene somehow ‘unnatural’. This has caused concern

among health professionals that everyday life hygiene behaviours,

which are the foundation of public health, are being undermined. In

response to the need for effective hygiene in home and everyday life

settings, the International Scientific Forum on Home Hygiene has

developed a "risk-based" or targeted approach to home hygiene that

seeks to ensure that hygiene measures are focussed on the places,

and at the times most critical for infection transmission. Whilst

targeted hygiene was originally developed as an effective approach

to hygiene practice, it also seeks, as far as possible, to sustain

"normal" levels of exposure to the microbial flora of our

environment to the extent that is important to build a balanced

immune system.

Excessive body hygiene of internal ear canals

Excessive body hygiene of the

ear canals can result in infection or

irritation. The ear canals require less body hygiene care than other

parts of the body, because they are sensitive, and the body system

adequately cares for these parts. Most of the time the ear canals

are self-cleaning; that is, there is a slow and orderly migration of

the skin lining the ear canal from the eardrum to the outer opening

of the ear. Old earwax is constantly being transported from the

deeper areas of the ear canal out to the opening where it usually

dries, flakes, and falls out. Attempts to clean the ear canals

through the removal of earwax can

actually reduce ear canal cleanliness by pushing debris and foreign

material into the ear that the natural movement of ear wax out of

the ear would have removed.

Excessive body hygiene of skin

Excessive body hygiene of the skin can result in skin irritation.

The skin has a natural layer of oil, which promotes elasticity, and

protects the skin from drying. When washing, unless using

aqueous creams with compensatory

mechanisms, this layer is removed leaving the skin unprotected.

Excessive application of soaps, creams, and ointments can also

adversely affect certain of the natural processes of the skin. For

examples, soaps and ointments can deplete the skin of natural

protective oils and fat-soluble content such as cholecalciferol

(vitamin D3), and external substances can be absorbed, to disturb

natural hormonal balances.

Culinary and food hygiene

Culinary hygiene pertains to the practices related to food

management and cooking to prevent

food contamination, prevent food

poisoning and minimize the

transmission of disease to other foods,

humans or animals. Culinary hygiene practices specify safe ways to

handle, store, prepare, serve and eat food.

Culinary practices include:

-

Cleaning and

disinfection

of food-preparation areas and equipment (for example using

designated cutting boards for preparing

raw meats and

vegetables). Cleaning may involve use of

chlorine bleach,

ethanol,

ultraviolet light,

etc. for disinfection.

-

Careful avoidance of

meats contaminated by

trichina worms,

salmonella,

and other pathogens; or thorough cooking of questionable meats.

-

Extreme care in

preparing raw foods, such as

sushi and

sashimi.

-

Institutional

dish sanitizing

by washing with soap and clean water.

-

Washing of hands

thoroughly before touching any food.

-

Washing of hands

after touching uncooked food when

preparing meals.

-

Not using the same

utensils

to prepare different foods.

-

Not sharing

cutlery

when eating.

-

Not licking fingers

or hands while or after eating.

-

Not reusing serving

utensils that have been licked.

-

Proper

storage of food

so as to prevent

contamination by

vermin.

-

Refrigeration

of foods (and avoidance of specific foods in environments where

refrigeration is or was not feasible).

-

Labeling food to

indicate when it was produced (or, as food manufacturers prefer,

to indicate its

"best before" date).

-

Proper disposal of

uneaten food and packaging.

Personal service hygiene

Personal service hygiene pertains to the practices related to the

care and use of instruments used in the administration of personal

care services to people:

Personal hygiene practices include:

-

Sterilization of

instruments used by service providers including

hairdressers,

aestheticians,

and other service providers.

-

Sterilization by

autoclave

of instruments used in

body piercing and

tattoo marking.

-

Cleaning hands.

History of hygienic practices

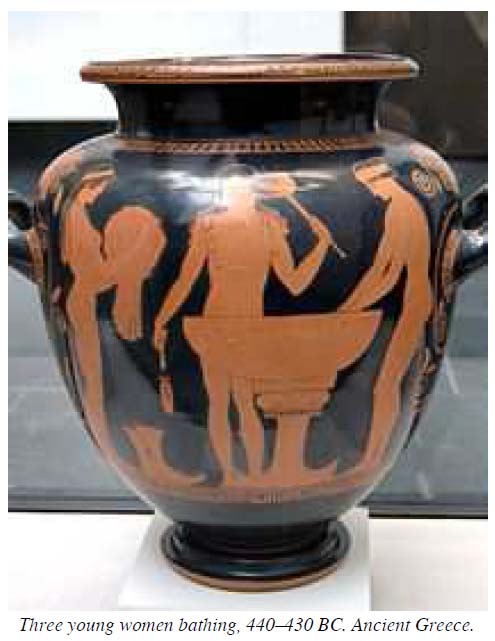

The earliest written account of Elaborate codes of hygiene can be

found in several Hindu texts, such as the

Manusmriti and the Vishnu Purana.

Bathing is one of the five Nitya karmas

(daily duties) in Hinduism, and not performing it leads to sin,

according to some scriptures.

Regular bathing was a hallmark of

Roman civilization. Elaborate

baths were constructed in urban areas to

serve the public, who typically demanded the infrastructure to

maintain personal cleanliness. The complexes usually consisted of

large, swimming pool-like baths, smaller cold and hot pools, saunas,

and spa-like facilities where individuals could be depilated, oiled,

and massaged. Water was constantly changed by an aqueduct-fed

flow. Bathing outside of urban centers involved smaller, less

elaborate bathing facilities, or simply the use of clean bodies of

water. Roman cities also had large sewers,

such as Rome's Cloaca Maxima, into

which public and private latrines drained. Romans didn't have

demand-flush toilets but did have some toilets with a continuous

flow of water under them. (Similar toilets are seen in Acre

Prison in the film Exodus.)

Until the late 19th Century, only the elite in Western cities

typically possessed indoor facilities for relieving bodily

functions. The poorer majority used communal facilities built above

cesspools in backyards and courtyards.

This changed after Dr. John Snow

discovered that cholera was

transmitted by the fecal contamination of water. Though it took

decades for his findings to gain wide acceptance, governments and

sanitary reformers were eventually convinced of the health benefits

of using sewers to keep human waste from contaminating water. This

encouraged the widespread adoption of both the flush toilet

and the moral imperative that bathrooms should be indoors and as

private as possible.

Islamic hygienical jurisprudence

Since the 7th century,

Islam has always placed a strong emphasis

on hygiene. Other than the need to be ritually clean in time for the

daily prayer (Arabic: Salat)

through Wudu and Ghusl,

there are a large number of other hygiene-related rules governing

the lives of Muslims. Other issues include the Islamic

dietary laws. In general, the

Qur'an advises Muslims to uphold high

standards of physical hygiene and to be ritually clean whenever

possible.

Hygiene in medieval Europe

Contrary to popular belief and although the Early Christian leaders,

such as Boniface I, condemned bathing as unspiritual,

bathing and sanitation

were not lost in Europe with the collapse of the Roman Empire.

Soap making first became an

established trade during the so-called "Dark Ages".

The Romans used scented

oils (mostly from Egypt), among

other alternatives.

Northern Europeans were not in the habit of bathing: in the ninth

century

Notker the Stammerer,

a Frankish monk of St Gall, related a disapproving anecdote that

attributed ill results of personal hygiene to an Italian fashion:

There was a certain deacon who followed the habits of the Italians

in that he was perpetually trying to resist nature. He used to take

baths, he had his head very closely shaved, he polished his skin, he

cleaned his nail, he had his hair cut as short as if it were turned

on a lathe, and he wore linen underclothes and a snow-white shirt.

Secular medieval texts constantly refer to the washing of hands

before and after meals, but Sone de Nansay, hero of a 13th-century

romance, discovers to his chagrin that the Norwegians do not wash up

after eating. In the 11th and 12th centuries, bathing was essential

to the Western European upper class: the

Cluniac

monasteries to which they resorted or retired were always provided

with bathhouses, and even the monks were required to take full

immersion baths twice a year, at the two Christian festivals of

renewal, though exhorted not to uncover themselves from under their

bathing sheets. In 14th century Tuscany, the newlywed couple's bath

together was such a firm convention one such couple, in a large

coopered tub, is illustrated in fresco in the town hall of San

Gimignano.

Bathing had fallen out of fashion in Northern Europe long before the

Renaissance, when the communal public

baths of German cities were in their turn a wonder to Italian

visitors. Bathing was replaced by the heavy use of sweat-bathing and

perfume, as it was thought in

Europe that water could carry disease into the body through the

skin. Bathing encouraged an erotic atmosphere that was played upon

by the writers of romances

intended for the upper class; in the tale of Melusine

the bath was a crucial element of the plot. "Bathing and grooming

were regarded with suspicion by moralists, however, because they

unveiled the attractiveness of the body. Bathing was said to be a

prelude to sin, and in the penitential of Burchard of Worms

we find a full catalogue of the sins that ensued when men and women

bathed together." Medieval church authorities believed that

public bathing created an environment

open to immorality and disease; the 26 public baths of Paris in the

late 13th century were strictly overseen by the civil authorities.

At a later date Roman Catholic Church

officials even banned public bathing in an unsuccessful effort to

halt syphilis epidemics from

sweeping Europe.

Modern sanitation was not widely adopted until the 19th and 20th

centuries. According to medieval historian Lynn Thorndike, people in

Medieval Europe probably bathed more than

people did in the 19th century. Sometime after Louis Pasteur's

experiments proved the germ theory of disease

and Joseph Lister and others put

them into practice in sanitation,

hygienic practices came to be regarded as synonymous with

health, as they are in modern times.

Industrial society

A

social hygiene movement

in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, sometimes including

mental hygiene (now mental health),

sexual hygiene and racial hygiene movements, was an attempt by

Progressive-era reformers to

prevent and control disease by changing the public's habits through

the use of scientific research

methods and modern media techniques. It was also based in part on

eugenics, and by the 1930s

thousands of forced sterilizations of people deemed undesirable took

place in America each year. After 1945 when the Nazis had taken it

even further, the movement was largely discredited. The drive for

cleanliness persisted, however, particularly cleanliness in

children. This showed many benefits such as reduced child mortality

rates. It also became increasingly commercialized, however, and may

have contributed to environmental pollution, resistance to

antibiotics, and even restricting the development of the immune

system leading to increased incidence of diseases such as

asthma or allergies.

Information society

In connection with the development of the

information society, appeared

information pollution, evolving

information ecology - associated with

informational hygiene.

what is Sanitation ?

Sanitation is the

hygienic

means of promoting health through

prevention of human contact with

the hazards of wastes

as well as the treatment and proper disposal of sewage

or wastewater. Hazards can be

either physical, microbiological,

biological or chemical agents of disease. Wastes that can cause

health problems include human and animal excreta, solid wastes,

domestic wastewater (sewage, sullage, greywater), industrial wastes

and agricultural wastes. Hygienic means of prevention can be by

using engineering solutions (e.g., sewerage, wastewater

treatment, stormwater drainage, solid

waste management, excreta management), simple technologies (e.g.,

pit latrines, dry toilets,

UDDTs, septic tanks),

or even simply by personal hygiene practices (e.g., hand

washing with soap, behavior change).

The

World Health Organization

States that:

"Sanitation generally refers to the provision of facilities and

services for the safe disposal of human urine and feces. Inadequate

sanitation is a major cause of disease world-wide and improving

sanitation is known to have a significant beneficial impact on

health both in households and across communities. The word

'sanitation' also refers to the maintenance of hygienic conditions,

through services such as garbage collection and wastewater disposal.

Sanitation includes all four of these engineering infrastructure

items (even though often only the first one is strongly associated

with the term "sanitation"):

-

Excreta management

systems

-

Wastewater management

systems

-

Solid waste

management systems

-

Drainage systems for

rainwater, also called stormwater drainage

Despite the fact that sanitation includes wastewater

treatment, the two terms are often use side by side: people tend to

speak of sanitation and wastewater management which is why

the differeantiation is also made in the sub-headings in this

article. The term sanitation has been connected to several

descriptors so that the terms sustainable sanitation, improved

sanitation, unimproved sanitation, environmental sanitation, on-site

sanitation, ecological sanitation, dry sanitation are all in use

today. Sanitation should be regarded with a systems approach in mind

which includes collection/containment, conveyance/transport,

treatment and disposal or reuse.

Wastewater management

Collection

The standard sanitation technology in urban areas is the collection

of

wastewater

in sewers, its treatment in wastewater treatment plants

for reuse or disposal in rivers,

lakes or the sea. Sewers are either combined with storm

drains or separated from them as

sanitary sewers. Combined sewers

are usually found in the central, older parts or urban areas. Heavy

rainfall and inadequate

maintenance can lead to combined sewer overflows or sanitary

sewer overflows, i.e., more or less

diluted raw sewage being

discharged into the environment. Industries often discharge

wastewater into municipal sewers, which can complicate wastewater

treatment unless industries pre-treat their discharges.

The high investment cost of conventional wastewater collection

systems are difficult to afford for many

developing countries. Some countries have

therefore promoted alternative wastewater collection systems such as

condominial sewerage, which uses pipes with smaller diameters at

lower depth with different network layouts from conventional

sewerage.

Treatment

For more details on this topic, see

Sewage

treatment.

Centralised treatment

In developed countries treatment of municipal wastewater is now

widespread, but not yet universal (for an overview of technologies

see

wastewater treatment). In

developing countries most wastewater is

still discharged untreated into the environment. For example, in

Latin America only about 15% of collected sewerage is being treated

(see water and sanitation in Latin America)

On-site treatment, decentralised treatment

In many suburban and rural areas households are not connected to

sewers. They discharge their wastewater into

septic tanks or other types of on-site

sanitation. On-site systems include drain fields,

which require significant area of land. This makes septic systems

unsuitable for most cities.

Constructed wetlands are another example

for a possible decentralised treatment option.

Disposal or reuse of treated wastewater

The reuse of untreated or partially treated wastewater in

irrigated agriculture is common in

developing countries. The reuse of treated wastewater in

landscaping, especially on golf courses, irrigated agriculture and

for industrial use is becoming increasingly widespread.

Types of sanitation

The term sanitation is connected with various descriptors to signify

certain types of sanitation systems. Here they are shown in

alphabetical order:

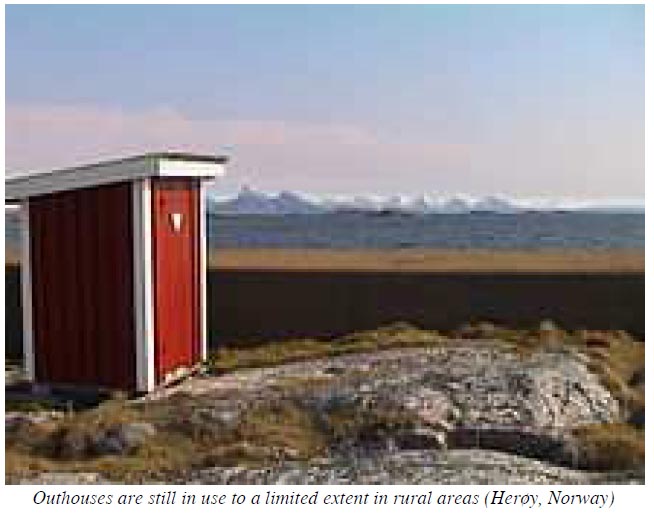

Dry sanitation

The term "dry sanitation" is somewhat misleading as sanitation as

includes handwashing and can never be "dry". A more precise term

would be "dry excreta management". When people speak of "dry

sanitation" they usually mean sanitation systems with

dry toilets

with urine diversion, in

particular the urine-diverting dry toilet

(UDDT).

Ecological sanitation

Ecological sanitation, which is commonly

abbreviated to ecosan, is an approach, rather than a technology or a

device which is characterized by a desire to "close the loop"

(mainly for the nutrients and organic matter) between sanitation and

agriculture in a safe manner. Put in other words: "Ecosan systems

safely recycle excreta resources (plant nutrients and organic

matter) to crop production in such a way that the use of

non-renewable resources is minimised". When properly designed and

operated, ecosan systems provide a hygienically safe, economical,

and closed-loop system to convert human excreta into nutrients to be

returned to the soil, and water to be returned to the land. Ecosan

is also called resource-oriented sanitation.

Environmental sanitation

Environmental sanitation is the control of environmental factors

that form links in disease

transmission.

Subsets of this category are solid waste management, water and

wastewater treatment,

industrial waste treatment and noise and

pollution control.

Improved and unimproved sanitation

Improved sanitation and unimproved

sanitation refers to the management of

human feces at the household level. This terminology is the

indicator used to describe the target of the Millennium

Development Goal on sanitation, by the

WHO/UNICEF

Joint Monitoring Programme for Water Supply and Sanitation.

Lack of sanitation

Lack of sanitation refers to the absence of sanitation. In practical

terms it usually means lack of toilets or lack of hygienic toilets

that anybody would want to use voluntarily. The result of lack of

sanitation is usually

open defecation (and open urination but

this is of less concern) with the associated serious public health

issues.

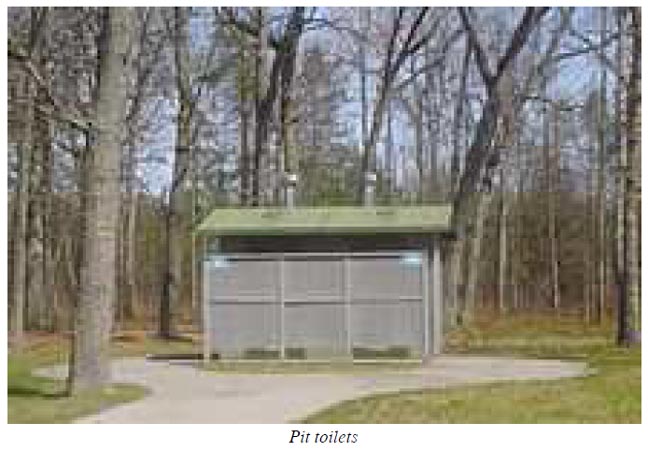

On-site sanitation

Onsite sanitation is the collection and treatment of waste is done

where it is deposited. Examples are the use of pit

latrines, septic tanks,

and Imhoff tanks

Sustainable sanitation

Sustainable sanitation is a term that has

been defined with five sustainability criteria by the

Sustainable Sanitation Alliance. In order

to be sustainable, a sanitation system has to be not only (i)

economically viable, (ii) socially acceptable, and (iii) technically

and (iv) institutionally appropriate, it should also (v) protect the

environment and the natural resources. The main objective of a

sanitation system is to protect and promote human health by

providing a clean environment and breaking the cycle of disease.

clean Toilets

A toilet is a

sanitation fixture used primarily for the

disposal of human urine and feces. They are often found in a small

room referred to as a toilet, bathroom or lavatory.

A toilet can be designed for people who prefer to sit (on a toilet

pedestal) or for people who prefer to squat (over a squatting

toilet). Flush toilets, which are

common in many parts of the world (particularly in more affluent

countries or regions), may be connected to a nearby septic

tank or more commonly in urban areas via

"large" (3–6 in or 7.6–15.2 cm) sewer pipe connected to a

sewerage pipe system. The water and waste

from many different sources is piped in large pipes to a more

distant sewage treatment plant or

wastewater treatment plant. Dry toilets,

including pit latrines and

composting toilets require no or little

water with excreta being removed manually or composted

in situ. Chemical toilets or

mobile dry toilets can be used in

mobile and many temporary situations where there is no access to

sewerage. Some types of toilets are more commonly referred to as

latrines, for example the "pit

latrine", and for most people the term

"toilet" has a cleaner more upmarket connotation than the word

"latrine".

Ancient civilizations used toilets attached to simple flowing water

sewage systems included those of the

Indus Valley Civilization, e.g.,

Harappa and Mohenjo-daro

which are located in present day India and Pakistan and also the

Romans and Egyptians.

Although a precursor to the flush toilet system which is widely used

nowadays was designed in 1596 by John Harington,

such systems did not come into widespread use until the late

nineteenth century. Thomas Crapper

was one of the early makers of flush toilets in England.

Diseases, including

cholera, which still affects some 3

million people each year, can be largely prevented when effective

sanitation and water treatment prevents fecal matter from

contaminating drinking water

supplies.

History

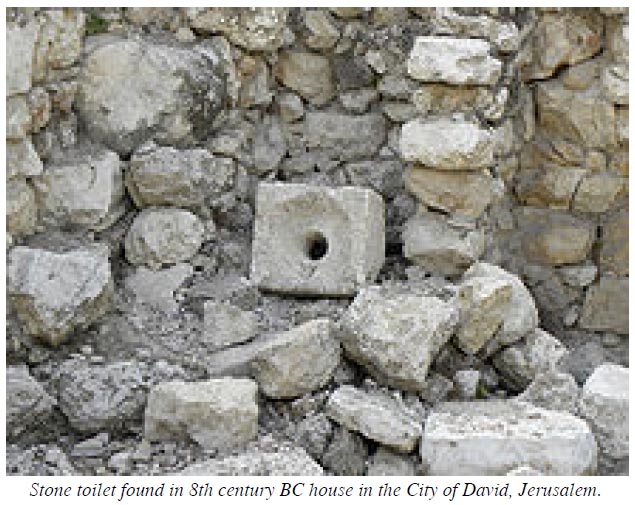

Ancient civilizations

According to Teresi et al. (2002)

The third millennium BC was the "Age of Cleanliness." Toilets and

sewers were invented in several parts of the world, and

Mohenjo-Daro circa 2800 BC had some of

the most advanced, with lavatories built into the outer walls of

houses. These were primitive "Western-style" toilets made from

bricks with wooden seats on top. They had vertical chutes, through

which waste fell into street drains or cesspits. Sir Mortimer

Wheeler, the director general of

archaeology in India from 1944 to 1948, wrote, "The high quality of

the sanitary arrangements could well be envied in many parts of the

world today."

The toilets at

Mohenjo-Daro,

built about 2600 BC and described above, were only used by the

affluent classes. Most people would have squatted over old pots set

into the ground or used open pits. The people of the Harappan

civilization in Pakistan and northwestern

India had primitive water-cleaning toilets that used flowing water

in each house that were linked with drains covered with burnt clay

bricks. The flowing water removed the human wastes.

Early toilets that used flowing water to remove the waste are also

found at

Skara Brae

in Orkney, Scotland, which was

occupied from about 3100 BC until 2500 BC. Some of the houses there

have a drain running directly beneath them, and some of these had a

cubicle over the drain. Around the 18th century BC, toilets started

to appear in Minoan Crete,

Egypt in the time of the Pharaohs

and ancient Persia. In

Roman civilization, toilets using flowing

water were sometimes part of public bath houses.

In 2012, archaeologists founded what is believed to be Southeast

Asia's earliest latrine during the excavation of a neolithic village

in the

Rạch Núi archaeological site, southern

Viet Nam. The toilet, dating back

1500 BC, yielded important clues about early Southeast Asian

society. More than 30 preserved feces from humans and dogs

containing fish and shattered animal bones from the site provided a

wealth of information on the diet of humans and dogs at Rạch Núi and

on the types of parasites each had to contend with.

Roman toilets, like the ones pictured here, are commonly thought to

have been used in the sitting position. But sitting toilets only

came into general use in the mid-19th century in the Western world.

The Roman toilets were probably elevated to raise them above open

sewers which were periodically "flushed" with flowing water, rather

than elevated for sitting.

The Romans weren't the first civilisation to adopt a sewer system:

The Indus Valley civilisation had a rudimentary network of sewers

built under grid pattern streets, and it was the most advanced seen

so far.

Squat toilets (also known as an Arabic,

French, Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Iranian, Indian, Turkish or

Natural-Position toilet) are used by squatting rather than sitting

and are still used by the majority of the world's population.

There are several types of squat toilets, but they all consist

essentially of a hole in the ground or floor with provisions for

human waste.

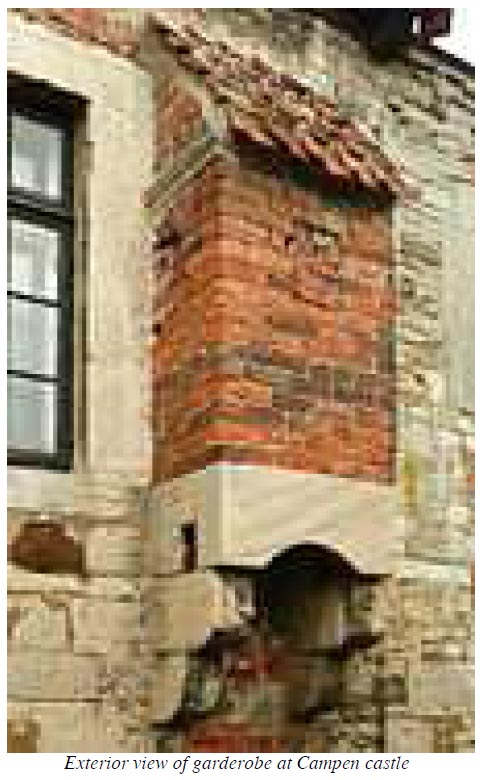

Early modern Europe

Chamber pots were in common use in Europe

from ancient times, even being taken to the Middle East by Christian

pilgrims during the Middle Ages. By the Early Modern era, chamber

pots were frequently made of china or copper and could include

elaborate decoration. They were emptied into the gutter of the

street nearest to the home.

During the

Victorian era,

British housemaids emptied household chamber pots into a "slop sink"

that was inside a housemaid's cupboard on the upper floor of the

house. The housemaids' cupboard also contained a separate sink, made

of wood with a lead lining to prevent chipping china chamber pots,

for washing the "bedroom ware". Once indoor running water was built

into British houses, servants were sometimes given their own

lavatory downstairs, separate from the family lavatory.

By the 16th century,

cesspits and cesspools were increasingly

dug into the ground near houses in Europe as a means of collecting

waste, as urban populations grew and street gutters became blocked

with the larger volume of human waste. Rain was no longer sufficient

to wash away waste from the gutters.

A pipe connected the latrine to the cesspool, and sometimes a small

amount of water washed waste through the pipe into the cesspool.

Cesspools would be cleaned out by tradesmen, who pumped out liquid

waste, then shovelled out the solid waste and collected it in

horse-drawn carts during the night. This solid waste would be used

as fertilizer.

The perception that human waste had value as fertilizer, and in

ammonia production, delayed the construction of a modern sewer

system as a replacement for the city's cesspool system. In the early

19th century, public officials and public hygiene experts studied

and debated the matter at length, for several decades.

The construction of an underground network of pipes to carry away

solid and liquid waste was only begun in the mid 19th-century,

gradually replacing the cesspool system, although cesspools were

still in use in some parts of Paris into the 20th century. The

growth of indoor plumbing, toilets and bathtubs with running water

came at the same time.

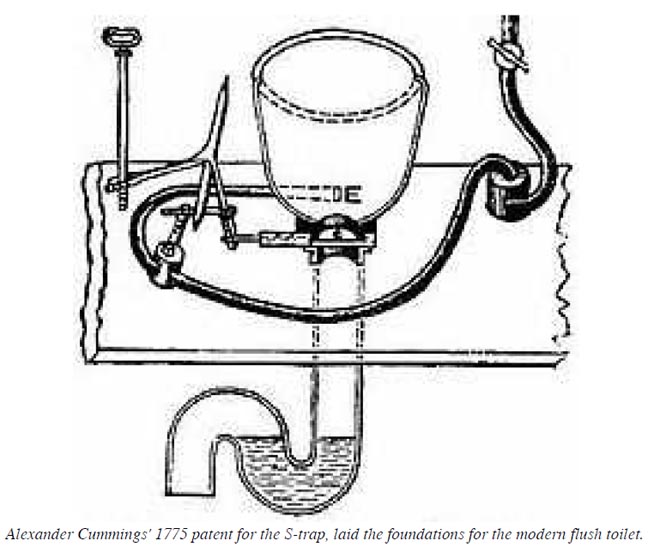

Development of the flush toilet

In 1596,

Sir John Harington

(1561–1612) published A New Discourse of a Stale Subject, Called

the Metamorphosis of Ajax, describing a forerunner to the modern

flush toilet installed at his house at Kelston.

The design had a flush valve to let water out of the tank, and a

wash-down design to empty the bowl. He installed one for his

godmother Queen Elizabeth I at

Richmond Palace, although she

refused to use it because it made too much noise. The Ajax was not

taken up on a wide scale in England,

but was adopted in France under

the name Angrez.

With the onset of the

Industrial Revolution and related

advances in technology, the flush toilet began to emerge into its

modern form. A crucial advance in plumbing, was the S-trap,

invented by Alexander Cummings in

1775, and still in use today. This device uses the standing water to

seal the outlet of the bowl, preventing the escape of foul air from

the sewer. His design had a sliding valve in the bowl outlet above

the trap. Two years later, Samuel Prosser applied for a British

patent for a "plunger closet".

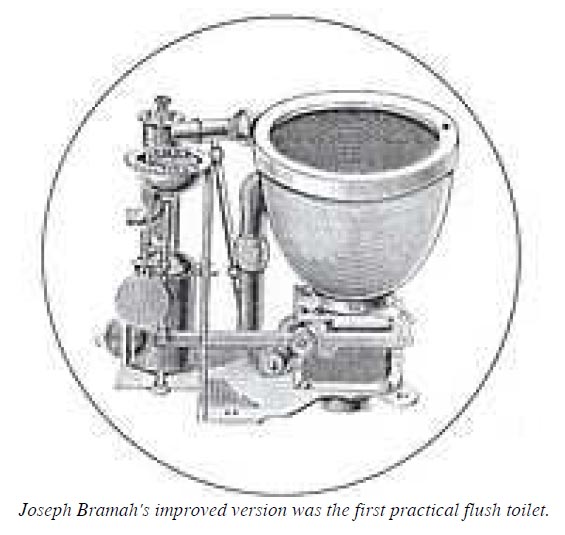

Prolific inventor

Joseph Bramah began his professional

career installing water closets (toilets) that were based on

Alexander Cumming's patented design of 1775. He found that the

current model being installed in London houses had a tendency to

freeze in cold weather. In collaboration with a Mr. Allen, he

improved the design by replacing the usual slide valve with a hinged

flap that sealed the bottom of the bowl.

He also developed a float valve system for the flush tank. Obtaining

the patent for it in 1778, he began making toilets at a workshop in

Denmark Street,

St Giles.

The design was arguably the first practical flush toilet, and

production continued well into the 19th century, used mainly on

boats.

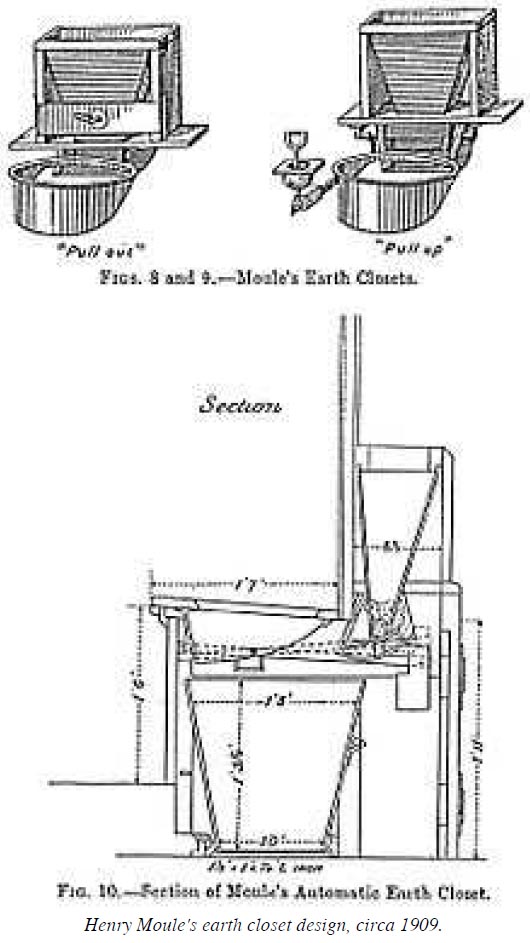

Dry earth closet alternative

Before the

flush toilet

became universally accepted, there were inventors, scientists, and

public health officials who

supported the use of dry earth closets. These were invented by the

English clergyman Henry Moule, who

dedicated his life to improving public sanitation after witnessing

the horrors of the cholera

epidemics of 1849 and 1854. Impressed by the insalubrity of the

houses, especially in the summer of 1858 (the Great Stink)

he invented what is called the dry earth system.

In partnership with James Bannehr, he took out a patent for the

process (No. 1316, dated 28 May 1860). Among his works bearing on

the subject were: ‘The Advantages of the Dry Earth System,’ 1868;

‘The Impossibility overcome: or the Inoffensive, Safe, and

Economical Disposal of the Refuse of Towns and Villages,’ 1870; ‘The

Dry Earth System,’ 1871; ‘Town Refuse, the Remedy for Local

Taxation,’ 1872, and ‘National Health and Wealth promoted by the

general adoption of the Dry Earth System,’ 1873.

His system was adopted in private houses, in rural districts, in

military camps, in many hospitals, and extensively in the

British Raj.

Ultimately, however, it failed to gain the same public support and

attention as the water closet, although the design remains today in

some parts of the world.

Industrial production

It was only in the mid-19th century, with growing levels of

urbanisation and industrial prosperity, that the flush toilet became

a widely used and marketed invention. This period coincided with the

dramatic

growth in the sewage system, especially

in London, which made the flush

toilet particularly attractive for health and sanitation reasons.

George Jennings established a business

manufacturing water closets, salt-glaze drainage, sanitary pipes and

sanitaryware at Parkstone Pottery in the 1840s, where he popularized

the flush toilet to middle class. At The Great Exhibition

at Hyde Park held from 1 May to 15

October 1851, George Jennings installed his Monkey Closets in the

Retiring Rooms of The Crystal Palace.

These were the first public toilets, and they caused great

excitement. During the exhibition, 827,280 visitors paid one penny

to use them; for the penny they got a clean seat, a towel, a comb

and a shoe shine. "To spend a penny" became a euphemism (now

archaic) for going to the toilet.

When the exhibition finished and moved to Sydenham, the toilets were

to be closed down. However, Jennings persuaded the organisers to

keep them open, and the toilet went on to earn over £1000 a year. He

opened the first underground convenience at

the Royal Exchange

in 1854. He received a patent in 1852 for an improved construction

of water-closet, in which the pan and trap were constructed in the

same piece, and so formed that there was always a small quantity of

water retained in the pan itself, in addition to that in the trap

which forms the water-joint. He also improved the construction of

valves, drain traps, forcing pumps and pump-barrels. By the end of

the 1850s building codes suggested

that most new middle-class homes in British cities were equipped

with a water closet.

Another pioneering manufacturer was

Thomas William Twyford, who invented the

single piece, ceramic flush

toilet. The 1870s proved to be a defining period for the sanitary

industry and the water closet; the debate between the simple water

closet trap basin made entirely of earthenware and the very

elaborate, complicated and expensive mechanical water closet would

fall under public scrutiny and expert opinion. In 1875, the

"wash-out" trap water closet was first sold and was found as the

public's preference for basin type water closets. By 1879, Twyford

had devised his own type of the "wash out" trap water closet, he

titled it the "National", and became the most popular wash-out water

closet.

By the 1880s, the free-standing water closet was sold and quickly

gained popularity; the free-standing water closet was able to be

cleaned more easily and was therefore a more hygienic water closet.

Twyford's "Unitas" model was free standing and made completely of

earthenware. Throughout the 1880s he submitted further patents for

improvements to the flushing rim and the outlet. Finally in 1888, he

applied for a patent protection for his "after flush" chamber; the

device allowed for the basin to be refilled by a lower quantity of

clean water in reserve after the water closet was flushed. The

modern pedestal "flush-down" toilet was demonstrated by Frederick

Humpherson of the Beaufort Works,

Chelsea, England

in 1885.

The leading companies of the period issued catalogues, established

showrooms in department stores and marketed their products around

the world. Twyford had showrooms for water closets in

Berlin, Germany; Sydney,

Australia; and Cape Town, South

Africa. The Public Health Act 1875

set down stringent guidelines relating to sewers, drains, water

supply and toilets and lent tacit government endorsement to the

prominent water closet manufacturers of the day.

Contrary to popular legend, Sir

Thomas Crapper did not invent the flush

toilet. He was, however, in the forefront of the industry in the

late 19th century, and held nine patents, three of them for water

closet improvements such as the floating ballcock.

His flush toilets were designed by inventor Albert Giblin, who

received a British patent for the "Silent Valveless Water Waste

Preventer", a siphon discharge system. Crapper popularized the

siphon system for emptying the tank, replacing the earlier floating

valve system which was prone to leaks.

Spread & further developments

Although flush toilets first appeared in Britain, they soon spread

to the

Continent.

The first such examples may have been the three "waterclosets"

installed in the new town house of banker Nicolay August Andresen

on 6 Kirkegaten in Christiania,

insured in January 1859.

The toilets were probably imported from Britain, as they were

referred to by the English term "waterclosets" in the insurance

ledger. Another early watercloset on the European continent, dating

from 1860, was imported from Britain to be installed in the rooms of

Queen Victoria in Ehrenburg Palace

(Coburg, Germany); she was the

only one who was allowed to use it.

In America, the chain-pull indoor toilet was introduced in the homes

of the wealthy and in hotels, soon after its invention in England in

the 1880s. Flush toilets were introduced in the 1890s.William

Elvis Sloan invented the

Flushometer in 1906, which used

pressurized water directly from the supply line for faster recycle

time between flushes.

The Flushometer is still in use today in public restrooms worldwide.

The vortex-flushing toilet bowl, which creates a self-cleansing

effect, was invented by Thomas MacAvity Stewart of

Saint John, New Brunswick in 1907.

Philip Haas of Dayton,

Ohio, made some significant

developments, including the flush rim toilet with multiple jets of

water from a ring and the water closet flushing and recycling

mechanism similar to those in use today.

Bruce Thompson, working for Caroma in

Australia, developed the Duoset cistern

with two buttons and two flush volumes

as a water-saving measure in 1980. Modern versions of the Duoset are

now available worldwide, and save the average household 67% of their

normal water usage.

Flush toilets

Operation

A typical flush toilet is a vitreous,

ceramic bowl containing water plus

plumbing made to be rapidly filled with

more water. The water in the toilet bowl is connected to a hollow

drain pipe shaped like an upside-down U connecting the drain. One

side of the U channel is arranged as a hollow siphon

tube longer than the water in the bowl is high. The siphon tube

connects to the drain. The bottom of the upside-down U-shaped drain

pipe limits the height of the water in the bowl before it flows down

the drain. If water is poured slowly into the bowl it simply flows

over the bottom of the upside-down U and pours slowly down the

drain—the toilet does not flush. The water in the bowl acts as a

barrier to sewer gas entering and as a receptacle for waste. Sewer

gas is vented through a vent pipe attached to the sewer line.

When a user flushes a toilet, a valve opens and allows the tank's

water to quickly enter the toilet bowl. This influx from the tank

causes the swirling water in the bowl to rapidly rise and fill the

U-shaped drain. The siphon tube mounted in the back of the toilet.

This full siphon tube starts the toilet's

siphon

action. The siphon action quickly (4–7 seconds) “pulls” nearly all

of the water and waste in the bowl and the on-rushing tank water

down the drain—it flushes. When most of the water has drained out of

the bowl, the continuous column of water up and over the bottom of

the upside-down U-shaped drain pipe (the siphon) is broken when air

enters the siphon tube. The toilet then gives its characteristic

gurgle as the siphon action ceases and no more water flows out of

the toilet. After flushing, the flapper valve in the water tank

closes; water lines and valves connected to the water supply refill

the toilet tank and bowl. The toilet is again ready for use.

At the top of the toilet bowl is a rim with many slanted drain holes

connected to the tank to fill, rinse and induce swirling in the bowl

when it is flushed. Mounted above the toilet is a large holding tank

with about (now) 1.6 to 1.2 US gallons (6.1 to 4.5 L) of water. This

tank is built with a large drain 2.0 to 3.0 inches (5.08 to 7.62 cm)

diameter hole at its bottom covered by a flapper valve that allows

the water to rapidly leave the holding tank. The

plumbing is built to allow entry of the

tank’s water into the toilet in a very short period. This water

pours through the holes in the rim and a siphon jet hole about 1.0

inch (2.54 cm) diameter in the bottom of the toilet. Other toilets

use a large hole in the front of the rim to allow fast filling of

the bowl.

Manufacture

A toilet's body is typically made from vitreous china, which starts

out as an aqueous suspension of various minerals called a

slip. It takes about 20 kilograms (44 lb)

of slip to make a toilet.

This slip is poured into the space between

plaster of Paris molds. The toilet bowl,

rim, tank and tank lid require separate molds. The molds are

assembled and set up for filling and the slip-filled molds sit for

about an hour after filling. This allows the plaster molds to absorb

moisture from the slip, which makes it semisolid next to the mold

surfaces but lets it remain liquid further from the surface of the

molds. Then, the workers remove plugs to allow any excess liquid

slip to drain from the cavities of the mold—this excess slip is

recycled for later use.

The drained-out slip leaves hollow voids inside the fixture, using

less material to keep it both lighter and easier to fire in a

kiln. This molding process allows the

formation of intricate internal waste lines in the fixture—the

drain's hollow cavities are poured out as slip.

At this point, the toilet parts without their molds look like and

are about as strong as soft clay. After about one hour the top core

mold (interior of toilet) is removed. The rim mold bottom (which

includes a place to mount the holding tank) is removed, and it then

has appropriate slanted holes for the rinsing jets cut, and the

mounting holes for tank and seat are punched into the rim piece.

Valve holes for rapid water entry into the toilet are cut into the

rim pieces. The exposed top of the bowl piece is then covered with a

thick slip and the still-uncured rim is attached on top of the bowl

so that the bowl and hollow rim are now a single piece. The bowl

plus rim is then inverted, and the toilet bowl is set upside down on